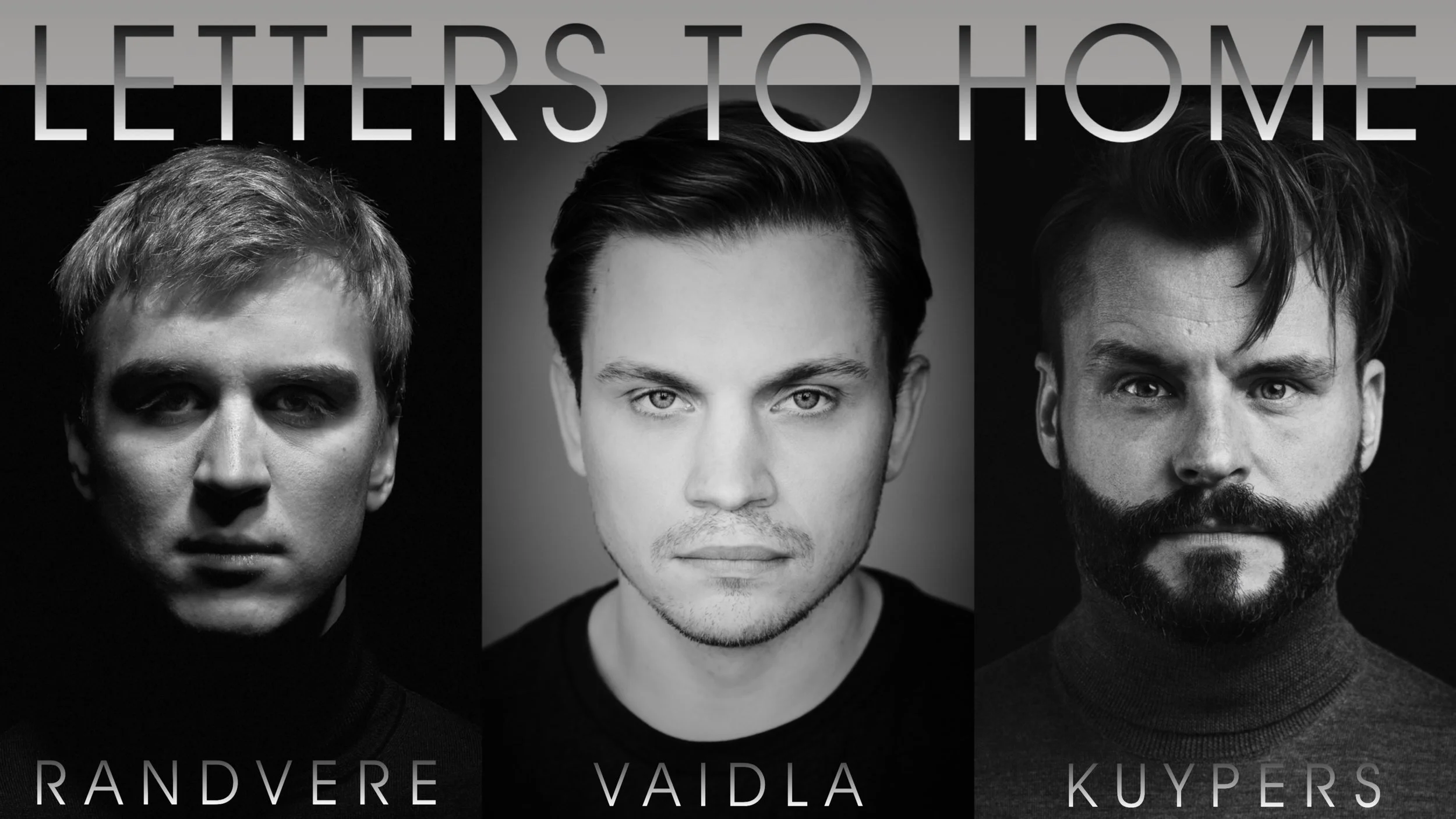

Letters to Home is a deeply moving program that draws upon the poignant and often heart-wrenching stories of individuals during the turbulent times of wartime. The touching accounts of refugees, heartfelt letters penned by young soldiers serving bravely in the trenches, and the intricate narratives of those who were captured provide powerful emotional insights that merit remembrance, particularly within the context of today's world, where such stories resonate deeply. The works of notable composers such as Mahler, Eisler, Butterworth, Somervell, Gurney, Warlock, and Poulenc intertwine these compelling stories through their evocative and rich music. ‘Kirjad Koju’ stands as a collaborative effort featuring the remarkably talented Estonian pianist Johan Randvere and the captivating Estonian actor Risto Vaidla, both of whom contribute to the program's profound impact.

——

The inspiration for the project „Letters to home“ came from the personal story of my Estonian mother-in-law. A part of her family fled with one of the last boats leaving Tallinn to Nazi Germany in 1944 to escape the Soviets. My girlfriend‘s grandfather Mart, who was 16 at the time, decided to stay in Estonia. It would be only 27 years later Mart eventually would be reunited with his mother…

Getting to know the story, our family found out that many Estonian refugees were taken to a camp in Geislingen, Germany. An Estonian village came about until the allied decided to break it up in 1949. Many went to the USA, Canada, Australia and so on to build a new life, a new family in a new location.

These stories planted a seed that came to fruition when I met pianist Johan Randvere. We talked about the subject, played through some music… Johan told Tim afterwards that also his family was affected. Risto Vaidla then joined the project and also he had a story running in the family: his grandmother Anu‘s deportation to Siberia.

As heartbreaking and sad as it was in these stories of the past 85 years or so, it‘s not a subject of the past unfortunately. These stories live on and new stories are being created everyday. It‘s with that idea that I approached the Ukrainian poet Pavlo Vyshebaba about his poem „To my daughter“:

Dear Tim,

Thank you so much for reaching out and for including my poem “To My Daughter” in your recital program. It’s deeply moving to know that my words resonate with you and your collaborators in such a meaningful way.

Poetry has a unique ability to bridge experiences and evoke empathy, and it’s a privilege to have my work contribute to such an important initiative.

I hope your recital inspires reflection and solidarity, especially during these challenging times.

Glory to Heroes

Warm regards,

Pavlo

PROGRAM

GEORGE BUTTERWORTH

Bredon Hill

The lads in their hundreds

On the idle hill of summer

Is my team ploughing

—

GUSTAV MAHLER

Der Tamboursg’sell

Revelge

—

HANNS EISLER

Die Heimkehr

—

ARTHUR SOMERVELL

White in the moon

There pass the careless people

—

IVOR GURNEY

In Flanders

—

GABRIEL FAURÉ

Les berceaux

—

PETER WARLOCK

The night

—

FRANCIS POULENC

Lune d’Avril

—

BASTIAAN WISTENBURG

Here dead we lie

Now hollow fires burn out to black

———

Letters, memoirs and poems

Helle Adams Kask emigrated to the United States with her sister and father in 1949.

In June 1941, in the late afternoon, three or four trucks full of Russian soldiers surrounded our house. I remember it as if it were yesterday. My father hid inside the water boiler, which had been kept empty for a hiding place. My 15-year-old sister hid also. Fortunately Mother spoke fluent Russian. The high ranking Russian officer told Mother to pack a few things for us, as they had orders to relocate our whole family to Siberia. We knew that meant certain death.

They searched the house but did not find Father. Mother cleverly offered them cognac, lots of it, and the soldiers got drunk. She begged them to give us more time to pack and they agreed to come back in the morning. The minute their trucks were out of sight we left to hide in the woods or with friends for the duration.

March 9, 1944 was a night God was protecting us again. The Russians bombed Tallinn, leaving half the buildings destroyed and nearly one thousand killed.

When the bombing finally ceased and we came up from the shelter the city was in flames. All the windows were blown out of all the houses, but our building was standing!

We had to leave, and through my uncle we were able to get on a German Red Cross Ship, called Moero. I can still see my dog, Sherry, running after us as we sat on the wagon and took one last look at home.

Mother had packed two-three suitcases with our clothes. It was supposed to be a temporary leave. We were sure we‘d return to our homeland in a couple of months. Other countries were going to help us! We boarded the Moero on September 21, 1944

The following day, about mid morning, as mother, father and my sister and I sat below, the ship suddenly shook. Immediately there was black smoke everywhere. We were scared. The ship had been hit by an aerial torpedo from a Soviet plane - a direct hit.

Mother, sister and I had life jackets. My father didn’t have one. The ship was sinking fast. Mother held my hand and father had to push us overboard. It was at least a 16-meter drop, and mother was not with me when I hit. I was alone in the black water. Since I was one of the few with a life jacket, people were trying to hang on to me. People were grabbing at my feet, pulling me under water.

I was nine years old, all by myself. The waves were huge and I was calling for my mother. Smoke covered the area, oil covered the water and was burning. Body parts, dead people were floating by, surrounding me. Nobody would help me… in situations of life and death, I learned, we will struggle to save ourselves first.

“Wake up, wake up,” I heard someone say. I opened my eyes and found myself in the lower bunk of a ship, under warm blankets. A German warship had picked up some survivors. They had dried my clothes, and I was able to get dressed. A nice officer took me up high on the bridge, so I could look around and hopefully see my parents and sister. I saw no familiar faces. None of my family was there.

Large pots of thin soup were brought in for us to eat but I had no cup, no spoon, so I couldn’t take any soup. I wasn’t able to eat for a long time until someone took pity and let me use his tin cup. People who had utensils would not share them with anyone—not even with children. That’s one of the horrors of war: everyone watches out only for themselves.

The ship docked in Germany, and the Germans took all survivors to a refugee camp. Two or three weeks went by and one day my sister appeared! At least we had each other. About two weeks later, our father showed up. Now we waited for mother to come. It took a long time to face the reality—mother had drowned. She was 37 years old.

————

Unknown American soldier in WWII

Dear Dot,

Did you ever receive the perfume that I sent you? A tent mate sent some home after I did, and he has just received a letter acknowledging it. Perhaps you have too, but it might be in another batch of letters that are taking a long time to get to me.

Some letters ago I told you about the reactions of some of the men to news they received from home. It still keeps on happening and turns some of the boys into men. When the test comes, these will be the men who feel that they have very little to lose, and will become either heroes, or dead men.

This, my darling, is another one of those letters that started out as an exercise in two-fingered typing and became lost somewhere. I seem to hear you say, “Don’t be afraid, I’ll always understand.” You always have, so I keep pouring my petty troubles in your ears.

For me there is only one hope left, that at the end of my journey, you will be there to welcome me. All the love, darling, that I haven’t been able to give you for these many months has been choked up in my heart. Tonight I must tell you. You are the ship that will carry me safely home, the armour that will shield me from harm, and the breath that comes into my body. Every wonderful African sunrise is the light that shines from your eyes, and every sunset the curve of your lips. The lapping of the waves upon the shore was your voice whispering to me. There is nothing that is good and kind that crosses my path that doesn’t make me think of you. I’m hungry and thirsty, I’m tired and weary, I’m savage and beastly—I’m all that is wretched, only because we are apart.

You have created storms in my breast whose fury if unloosed would have torn us both apart. I loved you even when I thought I hated. I’m just trying to say what has been said a million times before by poets and singers and said so much better. Sweetheart, I love you.

Bill

————

Michael Andrew Scott, 1916 - 1941, was killed over the English Channel.

Dear Daddy,

As this letter will only be used after my death, it may seem a somewhat macabre document, but I do not want you to look on it in that way. I have always had a feeling that our stay on earth, that thing which we call ‘Life', is but a transitory stage in our development, and that the dreaded monosyllable Death' ought not to indicate anything to be feared. I have had my fling and must now pass on to the next stage, the consummation of all earthly experience. So don't worry about me;

I shall be all right.

I would like to pay tribute to the courage which you and mother have shown, and will continue to show, in these tragic times. It is easy to meet an enemy face to face, and to laugh him to scorn, but the unseen enemies Hardship, Anxiety and Despair are a very different problem. You have held the family together as few could have done, and I take off my hat to you.

Now for a bit about myself. You know how I hated the idea of War, and that hate will remain with me forever. What has kept me going is the spiritual force to be derived from music, its reflections of my own feelings, and the power it has to uplift a soul above earthly things. Mark" has the same experience as I have in this though his medium of encouragement is Poetry. Now I am off to the source of Music, and can fulfil the vague longings of my soul in becoming part of the fountain whence all good comes. I have no belief in a personal God, but I do believe most strongly in a spiritual force which was the source of our being, and which will be our ultimate goal. If there is anything worth fighting for, it is the right to follow our own paths to this goal and to prevent our children from having their souls sterilised by Nazi doctrines. The most horrible aspect of Nazism is its system of education, of driving instead of leading out, and of putting State above all things spiritual. And so I have been fighting.

All I can do now is to voice my faith that this war will end in victory, and that you will have many years before you in which to resume normal civil life. Good luck to you!

Mick.

———

Anu Vaidla‘s deportation to Siberia

My grandmother was four years old when, in March 1949, she was deported along with her brother, mother, and grandmother from the village of Sinimaa in Hiiumaa. They were taken by ship from Lehtma harbor to Tallinn. From there, they were loaded into cattle cars and sent from the Baltic Station to Siberia. At first, they lived in an earthen hut, but later they were moved to a house where they had a single room. The room had a Russian stove, a bunk bed next to it where my grandmother and her brother slept, and a makeshift bed for their mother, made by placing wooden logs on the floor with a board and a mattress on top. The toilet was outside, made of three willow-branch walls woven together for some privacy, but it had no door.

In the village, they had their own community, a children’s home, and a large library. My grandmother remembers her first teacher as a very beautiful but very strict woman. When the announcement was made that Stalin had died, all the children in the class were expected to cry. However, my grandmother had heard a different story at home, so she didn’t cry. The teacher dragged her by the ears into a corner and beat her with doll heads. Crying, my grandmother went home, where her mother comforted her by saying, “Stalin is dead; things can’t get any worse now.”

When their mother was taken away to work in a mine, the children were supposed to go to an orphanage, but the local Estonians arranged for them to live with other Hiiumaa families instead. However, the situation turned into something like Cinderella and the wicked stepmother. These people were wealthier, with their own house, sewing machines, and livestock, but my grandmother was made to wash the mistress’s rags.

They had sheep, and one time when a sheep went missing, my grandmother and her brother had to search for it all night to avoid being beaten, as physical punishment was common in that household. Aunt Herta sent packages from Estonia for my grandmother and her brother, with socks, gloves, and hats, but the stepmother kept all the packages for herself. Once, when her brother went to collect a package, he decided to take one pair of gloves for them so they wouldn’t be so cold. Later, when a letter came asking if they had received all the socks and gloves, the stepmother found out. She tied Enn to a bench and beat him with sticks so badly that his kidneys were injured—this was done to an 11-year-old boy.

Sometime after Stalin’s death, a law was passed allowing children under 16 to return to Estonia. Aunt Herta came for them with an official document permitting her to retrieve Enn and Anu Reha within a year and a half. Herta didn’t speak a word of Russian, so she had their address written on a large piece of plywood in Russian. She traveled by train to Moscow, then to Novosibirsk, and finally took a bus to the village of Darski. They left Siberia in August 1954, when my grandmother was nine years old. She was completely wild at that time, and her brother wasn’t much better. Their aunt struggled with them, especially when it came to boarding the right train. At first, they behaved like savages—if their aunt left bread on the table and stepped out of the room, they would grab it, climb out the window, and eat it somewhere far away, fearing it might be taken from them.

My grandmother’s mother returned to Estonia in October 1955 but died of cancer on December 22 of the same year. Her condition was so severe that my grandmother wasn’t allowed to see her, and the first time she saw her mother again was in her coffin.

My grandmother went to live with her Uncle Paul in Hiiumaa and attended Lauka School, starting in the 4th grade. She graduated from Lauka School in 1959 and then moved on to Kärdla Secondary School for the 8th grade. Later, she wanted to attend a state-supported school in Tallinn, which she did because she felt like a burden to her uncle, who already had three children to care for.

Today, my grandmother turned 80 years old.

————

A.Alliksaar (1964) “Time”

There are no good times, there are no bad

The present is all there is to be had.

What starts will never come to a stop.

Neither beauty nor ugliness is part of the plot.

There are no gloomy or laughing days.

Our moments the same - equal our days.

Life breeds life, it’s all the same.

Chronos must have toys for his game.

There is no future, there is no past,

There is only now: this too will pass.

Live in the moment before its done.

In the blink of an eye it will be gone.

No one ever lives in vain.

Even if reasons are seldom plain.

More or less, there’s no certainty

Life usually demands a fee.

There are no losses, there’s no decay.

Just each moment of every day.

Time past won’t fade it will always remain,

in a mind’s eye all will stay the same.

————

Marie Under “The refugee”

Amid sorrows, I fell asleep, burdened by hardship and pain.

Once more, I long to return…but the road is severed, in vain.

I waded through thistles up to my throat, slave-whips tore at my hands,

waves crashed fiercely on my right, mountains pressed tight on both lands.

For rest, only a roadside ditch, no shelter, not even a trace.

In my aching heart, an open wound, mourning a loved one’s face.

Just once more, I wish to find the path that leads me home,

to sleep at last in native soil, where tears no longer roam.

————

Mari-Liis Virkus arrived in Boston with her mother and brother on May 15, 1949.”

“For many years, I didn’t know what my father looked like. I didn’t ask my mother because it would have made her sad. But when Cold War politics softened she wrote to her son Mart, who was still in Estonia, and asked for a photo of my father. He looked just like my oldest brother, handsome. At the age of fifteen, I was proud to accept him as my father and I put his picture in my wallet.

In 1996 my brother Ants went to the KGB archives in Tallinn with a Russian translator, and located my father's case file. In the autumn of 1942 in Russia, my father had been accused of being a member of the Estonian national guard. He was found guilty and sentenced to ten years of forced labor and five years in exile. On January 20, 1943, he died at prison in Irkutsk.

I’ve heard many stories about our life in Estonia, but my own first memory is of my sixth birthday cake, which was decorated with whipped cream cake and red currants. This birthday is the last one I celebrated at home.

During the summer of 1944 the carpenters build wooden cases to transport our furniture, household goods, and extra clothes for the journey to Germany. With horse and carriage my brother Mart brought our cargo to Tallinn harbor in early September. Mart was sixteen years old at the time and wanted to stay in Estonia.

My aunts questioned my mother about leaving home alone with two young children. ‘You can always come back‘ mother replied, ,but you can’t always leave.’

I realized the finality of our leaving, because I wanted to throw my teddy bear overboard so he could swim back home.

The cargo ship with our crates sank in the Baltic Sea and the only things my mother regretted were the photo albums. Looking back, I also wish we would have had the photos of father and our family.

When mother died, we returned to Estonia to bury her ashes at the old burial place in Vändra. The stonecutter chiseled my father’s name and „died in Siberia“ in the gray stone; under my mother’s name, „died in America“

I sketched a teapot, which is engraved on the stone as a symbol of warmth, politeness, love—-my mother

————

„To my daughter“ by Ukrainian soldier Pavlo Vyshebaba to his daughter (2022)

Don't write about the war to me,

Just answer: is there a garden near?

Do snails crawl on grass, and do you hear

cicadas singing, grasshoppers flee?

In faraway lands what do they call

their cats, what names did you hear?

The thing I wanted the most is to clear

your letters from sorrow, remove it all.

Do cherry trees already have flowers?

If someone brings a bouquet you like,

Don't tell them about scary missile strike,

instead, talk more of this life of ours.

Please invite all the people you found

to visit Ukraine when this war is over,

We'll show them our gratitude for knowing

our children were safe and sound.

————

Kirjad, mälestused ja luuletused

Helle Adams Kask

1941. aasta juunis, ühel hilisõhtupoolikul, piiras meie maja ümber kolm või neli vene sõduritega täidetud veoautot. Mäletan seda, nagu oleks see olnud alles eile. Mu isa peitis end veeboilerisse, mida peidukohaks tühjana hoiti. Kõrge aukraadiga vene ohvitser käskis emal pakkida kaasa mõned asjad, sest neil olid orderid kogu meie perekonna Siberisse saatmiseks. Me teadsime, et see tähendaks kindlat surma.

Nad otsisid maja läbi, aga isa üles ei leidnud. Ettenägelikult pakkus ema neile konjakit, hästi palju, ja sõdurid jäid purju. Ta palus neil anda meile pakkimiseks hommikuni aega, nad olid nõus. Samal hetkel kui nende veoautod vaateväljalt kadusid, läksime metsa ja sõprade juurde peitu…

09. märts 1944 oli öö, mil jumal meid jälle kaitses. Venelased pommitasid Tallinna, jättes maha pooled majad purustatuna ja ligi tuhat tapetud inimest.

Kui pommitamine viimaks lõppes ja me varjendist välja tulime, oli linn leekides. Majade ak- nad olid enamikus kõik puruks, aga meie maja seisis püsti!

Olime sunnitud lahkuma ning mu onu abiga oli meil võimalik pääseda ühele Saksa Punase Risti laevale. Laeva nimi oli Moero. Ma näen ikka veel oma koera Sherryt meile järele jooksmas, kui me vankril istudes heitsime viimase pilgu oma kodule.

Ema oli kaasa pakkinud paar-kolm kohvrit riietega. Arvati, et lahkumine on ajutine. Olime kindlad, et mõne kuu pärast võime kodumaale tagasi pöörduda. Teised riigid tulevad meile appi!

Astusime Moero pardale 21.septembril 1944.

Järgmisel päeval, kui ema, isa ja õega all olime, laev järsku vappus. Kõik kohad olid musta suitsu täis. Olime kabuhirmus. Laev oli saanud Nõukogude lennukitorpeedoga otsetabamuse. Emal, minul ja õel olid päästevestid. Isal ei olnud. Laev vajus kiiresti. Ema hoidis mul käest kinni ja isa lükkas meid üle parda. Kukkumine oli oma kuusteist meetrit ning kui ma alla jõudsin, polnud ema enam minu kõrval. Ma olin üksinda mustavas vees, olin üheksa aastat vana ja täiesti üksi. Lained olid tohutud, ma hüüdsin ema. Suits kattis ümbrust, õli kattis vett. õli põles, mu ümber olid leegid. Mitte keegi ei aidanud mind. Elu ja surma vahel viibides sain teada, et igaüks võitleb kõigepealt enda eest.

“Ärka üles, ärka üles” kuulsin kedagi ütlemas. Tegin silmad lahti ja leidsin end alumisest laevakoist soojade tekkide alt. Saksa sõjalaev oli mõned ellujäänud üles korjanud. Nad olid mu riided ära kuivatanud ja ma sain end riidesse panna. Üks sõbralik ohvitser viis mind üles kaptenisillale, nii sain ma ringi vaadata ja lootsin näha oma vanemaid ja õde.

Ühtki minu perekonna liiget seal ei olnud. Meile toodi söögiks suurte pottidega suppi, aga mul ei olnud kruusi ega lusikat ja ma ei saanudki endale suppi tõsta. Mul polnud hulk aega võimalust süüa, kuni ühel mehel must kahju hakkas ning ta laskis mul oma plekk-kruusi kasutada. Inimesed, kel olid sööginõud, ei jaganud neid kellegagi! Isegi lastega mitte. See on üks sõja koledusi: igaüks on väljas ainult iseenda eest. Laev randus Saksamaal ja sakslased viisid ellujäänud põgenikelaagrisse.

Möödus kaks-kolm nädalat ja ühel päeval saabus kohale mu õde! Vähemalt meie olime teineteisel olemas. Umbes kaks nädalat hiljem ilmus välja isa. Nüüd ootasime ema tulekut.

Tegelikkusele näkkuvaatamine võttis kaua aega-ema oli uppunud. Ta oli 37 aastat vana.

Helle Adams Kask emigreerus koos õe ja isaga 1949.aastal USAsse.

————

Tundmatu sõdur

Kallis, Dot!

Kas sa said selle parfüümi kätte, mis ma sulle saatsin? Mu telgikaaslane saatis parfüümi koju peale mind ja ta sai just kirja, et see jõudis kohale. Äkki sa saatsid ka, aga sinu kiri viibib veel järgmises saadetiste portsus, mille minuni jõudminevõtab kauem aega.

Mõned kirjad tagasi rääkisin sulle, kuidas mõned mehed reageerisid kodust kuuldud uudistele. See kestab senini ja muudab nii mõnegi poisi meheks. Kui katseaeg kätte jõuab, siis nendest saavad need mehed, kel on vähe kaotada,väljudes sellest kas kangelase või langenuna.

See, mu kallis, on üks järjekordsetest kirjadest, mis algas lihtsast klaviatuuri toksimisest, kuid mis läks kusagile oma teed uitama. Ma kuulen sind ütlemast: „Ära karda, ma mõistan sind“. Sa oled alati mõistnud, mistõttu valan ma oma tühised mured sinu kõrvadesse. Minu jaoks on jäänud vaid üks lootus, et selle teekonna lõpus oled sina mind ootamas ja vastu võtmas. Kõik see armastus, mida ma pole saanud sulle kõik need kuud jagada, on lämmatades kogunenud mu südamesse.

Ma pean sulle täna ütlema. Sa oled laev, mis kannab mind turvaliselt koju; raudrüü, mis kaitseb mind ohu eest; ja hingetõmme, mis voolab mu kehasse. Iga imeline Aafrika päikesetõus on valgus, mis särab su silmades ja iga päikeseloojang su huulekaares. Kaldale kohisevad lained olid kui su hääl sosistamas mulle. Pole miskit head ega lahket, millega kokku puutun, mis ei meenutaks mulle sind. Mul on nälg ja janu, olen väsinud ja tüdinud, olen jõhkard ja elajalik – olen kõik, mis on armetu, sest oleme lahus.

Oled põhjustanud torme mu rinnus, mille raev vallapääsenuna oleks meid lahku rebinud. Ma armastasin sind ka siis, kui arvasin sind vihkavat. Ma püüan öelda seda, mida on palju paremini öelnud luuletajad ja lauljad miljoneid kordi varem.

Kullake, ma armastan sind.

Bill

————

Michael Andrew Scott, 1916-1941

Kallis, isake!

Kuna seda kirja kasutatakse vaid peale mu surma, võib see kirjatükk tundudamõnevõrra õudsena, kuid ma ei taha, et sa sellele nõnda vaataksid. Mul on alati olnud tunne, et meie viibimine siin maakeral, see asi, mida kutsume Eluks, on vaid mööduv etapp meie arengus, ning see kardetud ühesilbiline Surm ei peaks viitama millelegi hirmutavale. Ma olen saanud oma naudingu ja pean nüüd edasi liikuma järgmisse faasi, pannes punkti kõik sellele maisele kogemusele. Seega ära minu pärast muretse; minuga on kõik hästi.

Ma soovin avaldada tänu sinu ja ema vaprusele, mida olete üles näidanud, ning mida jätkuvalt neil traagilistel aegadel näitate. On lihtne kohata vaenlast näost näkku ja tema üle põlgusega naerda, kuid nähtamatud vaenlased nagu Kannatused, Mure ja Ahastus on vägagi teistmoodi probleem. Oled hoidnud pere koos nagu vaid vähesed oleksid suutnud ning selle eest müts maha su ees.

Nüüd natuke minust endast. Sa tead, et vihkasin ideed Sõjast ja see viha jääb minuga alatiseks. Mind on käivitanud vaid muusikast ammutatud vaimne jõud, mis peegeldab mu oma tundeid ning selle vägi, mis ülendab hinge kõrgemale kõigest maisest. Marki kogemus on selles sarnane, mis minul, kuigi tema julgustuse instrumendiks on Luule. Ma sukeldun nüüd Muusika lättesse, täites selle hägusa hingeigatsuse saada osaks allikast, kust kõik hea tuleb. Mul ei ole usku Jumala isikusse, kuid ma usun tugevalt vaimsesse jõusse, mis oli meie eksistentsi allikaks, ning mis on meie ülim eesmärk. Kui on miskit väärt, mille eest võidelda, siis on selleks meie õigus käia oma teed selle eesmärgini ja takistada meie laste hingede võimetuks tegemist natsi õpetuse poolt. Kõige kohutavam natsismi osa on selle haridussüsteem, ande ja võimekuse välja ajamine mitte välja toomine, ja asetades Riigi kõigest vaimsest ülevaks. Ja seega olen ma võidelnud.

Kõik, mis ma nüüd teha saan, on väljendada oma usku, et see sõda lõppeb võiduga, ja et sulle on antud veel aastaid, mil jätkata tavainimese elu.

Palju edu sulle!

Mick

————

Anu vaidla

Mu vanaema oli nelja aastane, kui ta märtsis 1949. aastal küüditati, koos venna, ema ja vanaemaga Hiiumaalt, Sinimaa külast.Viidi Lehtma sadamast laevaga Tallinna. Sealt edasi tapi vagunitesse, Balti jaamast Siberisse. Alguses elasid mõnda aega muldonnis, siis pandi nad elama majja, kus nende kasutuses oli üks tuba. Seal oli vene ahi, ahju kõrval nari, kus magasid vanaema ja ta vend. Emale oli tehtud voodi nii, et pandi puupakud maha, mille peal oli laud ja selle peal madrats. Vets oli õues pajuokstest punutud kolm seina, et ikka päris teiste ees ei peaks äda tegema. Ust ei olnud.

Neil oli seal oma küla, lastekodu, suur raamatukogu. Vanaemal on meeles, et ta esimene õpetaja oli väga ilus, kuid väga kuri naine. Kui kuulutati, et Stalin on surnud, siis pidid kõik lapsed klassis nutma, aga vanaema oli kodus hoopis teist juttu kuulnud ning ta ei nutnud, siis õpetaja tiris ta kõrvupidi nurka ja peksis nukkidega. Vanaema läks nuttes koju ja ema lohutas teda, et Stalin on surnud, enam hullemaks minna ei saa.

Kui ema viidi nende juurest ära, kuhugi kaevandusse tööle, siis lapsed pidid minema lastekodusse, aga eraldi, siis leppisid eestlased kokku, et nad läheksid ühtede teiste hiidlaste juurde elama, aga siis hakkas selline tuhkatriinu ja võõrasema suhe. Nemad olid rikkamad, nii et neil oli oma maja, õmblusmasinad ja koduloomad. Vanaema pidi siis perenaise kaltse pesema. Neil olid lambad, ükskord kui üks lammas ära kadus, siis pidid nad vennaga öö läbi seda lammast otsima, muidu oleksid nad Ennuga mõlemad peksa saanud, sest peksmine oli nende juures tavaline asi.

Tädi Herta saatis Eestist pakke vanaemale ja ta vennale – sokke, kindaid, mütse, kuid võõrasema võttis kõik pakid omale. Ükskord kui vend läks pakile järele, otsustas ta võtta ühe paari kindaid endale, et nad saaksid omale ka midagi, et nii külm ei oleks. Siis kui tuli ükskord kiri järgi, et kas te saite nii palju sokke ja kindaid kätte, siis võõrasema sai teada ning Enn seoti pingi külge kinni ja teda peksti keppidega nii, et neerud olid lahti. Noort 11 aastast poissi.

Millalgi pärast Stalini surma võeti vastu seadus, et alla 16 aastased lapsed saavad tagasi Eestisse tulla, siis tuli seesama tädi Herta neile järele. Tal oli ametlik dokument, et ta võib Ennule ja Anu Rehale järele minna pooleteise aasta jooksul. Herta ei osanud sõnagi vene keelt ja ta tuli neile järele nii, et lasi kirjutada suurelt vene keeles vineertükile nende aadressi. Tuli rongiga kõigepealt Moskvasse, sealt Novosibirski rongi peale, sealt edasi siis mingi bussiga Darski külla. Nad said tulema 1954. aasta augustis, vanaema oli siis 9 aastane. Ta oli olnud täiesti kasvatamatu tüdruk, vend natuke hullem, tädi oli nendega kimpus, et õige rongi peale saada. Nad olid alguses ikka täitsa metsalised, kohe kui tädi pani leiva lauale ja läks korraks teise teise tuppa, siis krabasid nad selle pihku ja läksid kohe aknast välja kuhugi eemale sööma, et mine sa tea, äkki võetakse käest ära. Vanaema ema jõudis Eestisse tagasi 1955 oktoobris, aga suri vähki sama aasta 22. detsembril, ema oli nii raskes seisus, et vanaemal ei lubatudki teda vaatama minna ja seega nägi teda alles kirstus.

Vanaema läks Hiiumaale onu Pauli juurde elama, läks Lauka kooli 4-sse klassi, 1959 lõpetas Lauka kooli. Sealt läks edasi Kärdla Keskkooli 8ndasse klassi, aga siis tahtis saada Tallinnasse riikliku ülalpidamisega kooli, kuhu ta ka läks, sest tundis ennast üleliigsena onu juures, kellel oli endal kolm last kasvatada.

Vanaema sai täna 80 aastaseks

———-

A. Aliksaar (1964) “Aeg”

Ei ole paremaid, halvemaid aegu.

On ainult hetk, milles viibime praegu.

Mis kord on alanud, lõppu sel pole.

Kestma jääb kaunis, kestma jääb kole.

Ei ole süngeid, ei naljakaid aegu.

Võrdsed on hetked, kõik nad on praegu.

Elul on tung kanda edasi elu,

jällegi Kronos et saaks mõne lelu.

Ei ole möödund või tulevaid aegu.

On ainult nüüd ja on ainult praegu.

Säilib, mis sattunud hetkede sattu.

Ainuski silmapilk teisest ei kattu.

Ei ole mõttetult elatud aegu.

Mõte ei pruugigi selguda praegu.

Vähemat, rohkemat olla ei võinuks.

Parajal määral saab elu meilt lõivuks.

Ei ole kaduvaid, kõduvaid aegu.

Alles jääb hetk, milles asume preagu.

Aeg, mis on tekkinud, enam ei haju,

kui seda jäävust ka meeled ei taju.Marie Under

————

Marie Under “Põgenik”

Murede keskel ma magasin,

vahel vaevade,

Kord veel tahaksin tagasi…

Ära lõigat on tee.

Kahlasin kaelani ohakais,

orjavits veristas käed,

paremal ahistas laini pais,

vasemal surusid mäed.

Puhkuseks piskuks vaid maanteekraav ——-

varju ei vähimat.

Valutas südames lahtine haav,

leinates lähimat.

Kord veel tagasi tahaksin

leida kodutee,

kodumullas siis magaksin

välja kõik silmavee.-

————

Mari-Liis Virkus Smyth

Aastaid ei teadnud ma, milline näeb välja mu isa. Emalt ma ei küsinud, see oleks teda väga kurvastanud. Kuid pärast külma sõja poliitika leevenemist kirjutas ema Eestisse jäänud Mardile ja küsis isa fotot. Isa nägi sel pildil välja väga mu vanema venna moodi-oli ilus mees. Seega siis alles viietesitkümneaastaselt võisin tunnistada oma isa ja panin pildi rahakotti.

Olen kuulnud palju lugusid meie elust Eestist, kuid minu enda esimene mälestus on mulle kuueaastaseks sünnipäevaks tehtud punaste sõstardega vahukooretort. See jäi ka mu viimaseks sünnipäevapeoks kodumaal. 1944.aasta suvel saagisid puusepad meie juures laudu, haamerdasid ja naelutasid, ühesõnaga valmistasid kaste, kuhu mahutada meie mööbel, kodukraam ja riided Saksamaale sõiduks.

Septembri alguses viis mu vend kogu laadungi hobusega Tallinna sadamasse. Mart oli tollal kuueteistkümneaastane ja tahtis Eestisse jääda…

Tädid uurisid emalt, kuidas ta mõtleb üksinda kahe väikese lapsega ära minna. Alati on võimalik tagasi tulla, aga alati ei ole võimalik ära minna, vastas ema.” Pärast ema surma tulime Eestisse, matsime ta tuha Vändra vanasse surnuaeda. Lasin hauakivile graveerida enda kujundatud teekannud, sümboliseerimaks soojust, viisakust, armastust- kõike seda, mis iseloomustab minu ema.

Mari-Liis Virkus, saabus oma ema ja vennaga Bostonisse 15.mail 1949.

————

Pavlo Vyshebaba „Minu tütrele“

“Ära räägi mulle sõjast”

Ära kirjuta mulle sõjast,

Lihtsalt vasta: kas seal on läheduses mõni iluaed?

Kas rohu sees roomavad teod, ja kas kuuled

tsikaadide laulu, rohutirtsude pagemist?

Kuidas nad kutsuvad kaugetel maadel

oma kasse, Mis nimesid oled sa kuulnud?

Kõige enam tahaksin su kirjadest

eemaldada kurbuse, ära kaotada see kõik.

Kas kirsipuudel on juba õied?

Kui keegi toob sulle lillekimbu, mis sulle meeldib, Ära räägi neile õudsetest mürsurünnakutest,

Vaid räägi neile meie eluolust.

Palun kutsu kõik inimesed, keda kohtad,

Ukrainat külastama, kui see sõda on läbi.

Siis väljendame neile oma tänulikkust teadmise eest,

Et me lapsed olid hoitud ja kaitstud.